A couple of years ago, I was teaching a group of high school freshmen about copyright.

In my library at the time, student art work filled many of the open spaces and shelves. I asked the art teacher to always label every piece with the student-artist’s name, as the kids certainly deserve the credit for all the hard work they put into the piece.

In the middle of my lesson, I turned around and pretended to notice the beautiful ceramic piece behind me for the first time. Commenting and complimenting the artwork, I then removed the student name placard and replaced it with one of my own. One with my name on it.

”You like this piece of artwork I did last night?” I asked the students.

Of course, they protested immediately. (It helps that I picked a piece done by a student who was in the class at the time!)

What I was doing, during my little stunt, was attempting to pass off another’s work as my own: the very essence of copyright infringement.

Making the copyright connection

What worries me as a teacher, librarian, and a parent, is that students so often miss this point. They don’t see that using someone else’s stuff in their own stuff is a violation of copyright. It is, essentially, unethical behavior.

When they do a Google search for an image, right-click on the image to copy it, and paste it into their own project, they’re really doing the same thing that I used to do in middle school when I would copy, word-for-word, chunks of text out of an encyclopedia and into a school report.

Yet, when you call students on this behavior, and point out that what they’re doing is, in effect, stealing from the original creator of the image or video or song or whatever, they look at you like you’re some ancient relic.

Is it really copyrighted?

One misconception about copyright: if it doesn’t have the copyright or trademark symbol next to it, it must be okay to use. Not so.

Under the U.S. copyright law (Title 17 of the U.S. Code), copyright/ownership is established as soon as the work is created. I click publish, the essay belongs to me. My finger pushes the shutter on my camera, the photo belongs to me. I record a song or piece of music, it belongs to me.

Yes, artists and creators can still officially file for copyright, but this is largely unnecessary anymore, except in certain cases.

One thing I always try to stress with students is that this law is to protect them as creators. It is not just a move to limit their ability to grab photos and images for their next PowerPoint presentation.

I’m pretty sure the student artist whose beautiful ceramic piece I “stole” would agree.

The Fair Use Exception

As with many laws, there are exceptions.

The Fair Use exception (Section 107 of the Copyright Act) allows for the use of copyrighted materials under certain circumstances, including literary criticism, reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.

While Fair Use is rather complex (as most legal language is!), it doesn’t need to be confusing. As parents of digital kids, the only use of the exception we really need to understand is the academic one.

Under Fair Use, students (and teachers) are allowed to use copyrighted materials for school work, considering these four factors:

1. “Purpose and character of the use”

Simply put, why are you using the material? Are you trying to make money off it? Then, sorry.

Is this for a school setting? Probably okay.

2. “Nature of the copyrighted work”

In general, the more creative the work (a song, poem, short fiction, graphic, unique photograph, movie clip, etc.) the more likely you will be violating copyright and Fair Use can’t be ‘claimed.’ On the other hand, using a more factual work (a news article, a technical report, etc.), would fall more easily under Fair Use.

3. “Amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.”

Whew. That’s a mouthful.

Basically this has to do with two things: how much of the work are you using, and how significant is this ‘part’ to the whole thing.

For example, using an entire song as the soundtrack to my presentation would not hold up under Fair Use, but using a 30-second clip would.

Another common example. For projects, kids love using sports logos, all of which are copyrighted. Here in Wisconsin, if I used the well-recognized Green Bay Packer “G” logo, but just altered the colors, I’m still using the most significant part of the original work: the iconic letter in that particular shape and orientation. Making it pink doesn’t give me the right to use it.

4. “Effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

[Man, will the legalese never end!]

Ok, this has to do with money and how much might be lost if I use the copyrighted work in my own thing.

If I’m taking a chunk of the work and selling it or giving it away, and that may impact the sales for the original owner, that’s not Fair Use.

Really, the best example of this actually relates to the adults. If a teacher makes 30 copies of a classic poem for use in her English class, clearly Fair Use.

If that same teacher takes a workbook (the kind that you are supposed to buy for each student every year) and makes 30 copies of some of the activities for class, that’s not meeting this 4th criteria of Fair Use. Potentially, it has a “market” impact on sales of that workbook. It would mean this school in particular would not be buying 30 copies of the workbook each year.

Funny, publishers don’t like that. Go figure.

Teaching good digital citizenship

So, if the Fair Use exception says that students can use copyrighted material, why limit them? Why teach them to find other sources when Google Image Search is the easiest way? Does it really matter? I mean, the law itself explicitly states the exceptions to itself!

My fear, as a teacher, is that we will train kids so well on what the exception to the law is that when they are no longer “covered” in an academic setting, they will use stuff that they shouldn’t be using in places where they shouldn’t be using it.

Even though kids can use copyrighted material, providing they meet the Fair Use criteria, why not encourage them to use copyright-free images, video, audio, etc., now.

Here are a few things we, as parents, can do to encourage using copyright-free materials

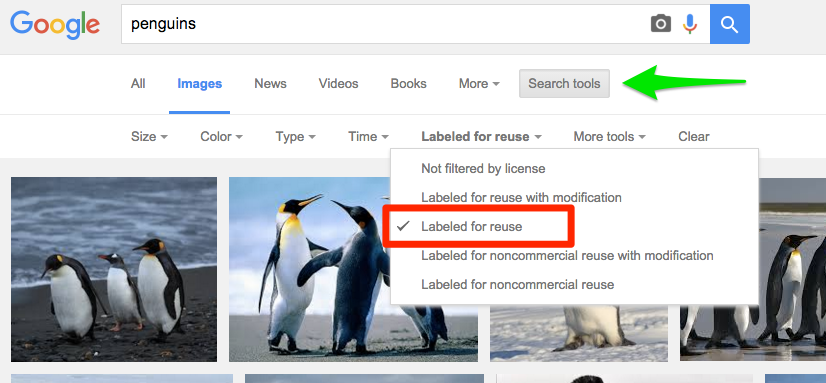

Google image filters

Within a Google Image search, you can filter only those photos and graphics where the creator has given permission for the image to be used.

To do this, start with the search itself, just as you normally would. Once the results come up, click on Search Tools, then Usage Rights. Select “Labeled for Reuse”, and the filter will re-sort the results.

Royalty-free image collection

With just a little more effort, kids can find the images they need in one of the many copyright-free collections online. The amount of royalty-free content is growing every day. For example, the New York Public Library just recently release over half a million digital images for public use.

Creative Commons

Creative Commons was developed as an easy way for creators to “give permission” for their works to be used, and to specify what they will and won’t allow. Artists, photographers, writers, and others can “stamp” their works with different licenses. Some search tools will let you filter by Creative Commons license, and you can look for the symbol as well.

Creative Commons was developed as an easy way for creators to “give permission” for their works to be used, and to specify what they will and won’t allow. Artists, photographers, writers, and others can “stamp” their works with different licenses. Some search tools will let you filter by Creative Commons license, and you can look for the symbol as well.

Create your own

Of course, the best way to avoid breaking copyright or accidentally using someone else’s work is to produce your own. Take your own pictures for backgrounds in a PowerPoint slide. Create your own music soundtrack using GarageBand or another online music creation tool.

Copyright at home

While our children may be getting some of this in school, this ethical use of other people’s intellectual property needs to be reinforced at home, too.

First, we must set good examples as parents. And, yes, this includes what we are sharing on social media. Or the Disney character we were going to use in the poster we are making for the PTA.

Start early talking about the connection between respecting the physical property of others and the digital property of others. This isn’t something we have to wait until middle or high school to start teaching.

Finally, encourage them to cite sources: giving credit when they use someone else’s stuff. No, teachers will not always require this on a project or assignment. And yes, this will eventually look like all that MLA/APA stuff that you suffered through in school.

But it sends a clear message that, if it’s not yours, be very careful how you use it.

•очешь продать авто? телеграм канал продажа и выкуп авто

Осознанное участие в азартных развлечениях — это принципы, направленный на предотвращение рисков, включая ограничение доступа несовершеннолетним .

Сервисы должны внедрять инструменты контроля, такие как лимиты на депозиты , чтобы минимизировать зависимость .

Регулярная подготовка персонала помогает реагировать на сигналы тревоги, например, частые крупные ставки.

вавада зайти

Предоставляются ресурсы консультации экспертов, где можно получить помощь при проблемах с контролем .

Следование нормам включает проверку возрастных данных для предотвращения мошенничества .

Задача индустрии создать условия для ответственного досуга, где удовольствие сочетается с вредом для финансов .

Greetings, explorers of unique punchlines !

Adult jokes that walk the line perfectly – http://jokesforadults.guru/ best jokes adult

May you enjoy incredible unique witticisms !

Хотите найти информацию о пользователе? Этот бот предоставит полный профиль мгновенно.

Используйте продвинутые инструменты для анализа цифровых следов в открытых источниках.

Узнайте место работы или активность через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

глаз бога пробить человека

Система функционирует в рамках закона , используя только общедоступную информацию.

Закажите расширенный отчет с геолокационными метками и списком связей.

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для исследований — результаты вас удивят !

Нужно собрать информацию о пользователе? Этот бот предоставит полный профиль мгновенно.

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для анализа публичных записей в соцсетях .

Выясните место работы или интересы через автоматизированный скан с верификацией результатов.

бот глаз бога телеграмм

Система функционирует в рамках закона , обрабатывая открытые данные .

Закажите расширенный отчет с геолокационными метками и списком связей.

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для исследований — результаты вас удивят !

Tired of average haircuts and inconsistent service?

It’s time to upgrade your grooming experience with the barber near me, best barbershop, and best haircut

Singapore has to offer. Whether you’re searching for

a sharp fade, a classic cut, or a full grooming package, finding the best haircut near me or best barbershop near me

can make all the difference in how you look and feel.

Singapore is home to a vibrant grooming scene, where both traditional barbers and upscale salons deliver world-class haircuts and styling.

If you’re looking for the best barber near me, you’ll find professionals who combine skill,

style, and precision to craft a look that suits your face and personality.

For those who prefer a more tailored experience, many of the best salon Singapore

options offer premium hair treatments, color services, and styling consultations.

When you search for a barber near me or a salon near me, don’t just settle

for convenience. Look for places that are known for delivering the best haircut in Singapore—spots with consistent reviews,

expert staff, and a commitment to quality.

So whether you’re prepping for an event, maintaining your style, or trying something bold and new, trust the best barbershop Singapore or best salon near me to bring your vision to life.

Book your appointment today and walk out looking and feeling your best.

¡Saludos, fanáticos del desafío !

Casino bonos de bienvenida directo a cuenta – http://bono.sindepositoespana.guru/# bono de bienvenida casino

¡Que disfrutes de asombrosas movidas brillantes !

Нужно найти информацию о пользователе? Наш сервис поможет полный профиль в режиме реального времени .

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для поиска цифровых следов в открытых источниках.

Выясните контактные данные или активность через систему мониторинга с верификацией результатов.

тг бот глаз бога бесплатно

Система функционирует в рамках закона , обрабатывая общедоступную информацию.

Получите расширенный отчет с геолокационными метками и графиками активности .

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для исследований — результаты вас удивят !

I have not checked in here for some time because I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I’ll add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend

Здесь предоставляется сведения по любому лицу, в том числе исчерпывающие сведения.

Архивы охватывают граждан разного возраста, профессий.

Данные агрегируются по официальным записям, подтверждая точность.

Нахождение производится по имени, что делает использование быстрым.

глаз бога найти телефон

Помимо этого доступны контакты и другая важные сведения.

Все запросы выполняются в соответствии с правовых норм, что исключает разглашения.

Обратитесь к этому сайту, чтобы найти искомые данные в кратчайшие сроки.

Как оформить карту иностранная карта для россиян для россиян в 2025 году. Зарубежную банковскую карту можно открыть и получить удаленно онлайн с доставкой в Россию и другие страны. Карты подходят для оплаты за границей.

ремонт стиральной машины ariston ремонт модуля стиральной машины

¡Hola, descubridores de fortunas !

Casino sin licencia espaГ±ola con torneos internacionales – п»їcasinosonlinesinlicencia.es casinos sin licencia

¡Que vivas increíbles jackpots impresionantes!

Хотите собрать информацию о человеке ? Этот бот предоставит детальный отчет в режиме реального времени .

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для анализа публичных записей в открытых источниках.

Узнайте контактные данные или интересы через автоматизированный скан с гарантией точности .

рабочий глаз бога телеграм

Бот работает с соблюдением GDPR, обрабатывая открытые данные .

Получите расширенный отчет с геолокационными метками и графиками активности .

Доверьтесь проверенному решению для digital-расследований — результаты вас удивят !

Хотите собрать информацию о пользователе? Наш сервис предоставит полный профиль мгновенно.

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для поиска публичных записей в соцсетях .

Узнайте место работы или интересы через автоматизированный скан с гарантией точности .

рабочий глаз бога телеграм

Бот работает в рамках закона , используя только общедоступную информацию.

Получите детализированную выжимку с геолокационными метками и списком связей.

Попробуйте проверенному решению для digital-расследований — точность гарантирована!

Animal Feed https://pvslabs.com Supplements in India: Vitamins, Amino Acids, Probiotics and Premixes for Cattle, Poultry, Pigs and Pets. Increased Productivity and Health.

New AI generator ai chat nsfw of the new generation: artificial intelligence turns text into stylish and realistic image and videos.

Mountain Topper https://www.lnrprecision.com transceivers from the official supplier. Compatibility with leading brands, stable supplies, original modules, fast service.

Hindi News https://tfipost.in latest news from India and the world. Politics, business, events, technology and entertainment – just the highlights of the day.

стиральная машина миля ремонт ремонт двигателя стиральной машины

testo taylan müzik uzun versiyon

UP&GO https://upandgo.ru путешествуй легко! Визы, авиабилеты и отели онлайн

ремонт платы стиральной машины ремонт стиральных машин недорого

Офисная мебель https://mkoffice.ru в Новосибирске: готовые комплекты и отдельные элементы. Широкий ассортимент, современные дизайны, доставка по городу.

Онлайн займы срочно https://moon-money.ru деньги за 5 минут на карту. Без справок, без звонков, без отказов. Простая заявка, моментальное решение и круглосуточная выдача.

Услуги массаж ивантеевка — для здоровья, красоты и расслабления. Опытный специалист, удобное расположение, доступные цены.

AI generator nsfw ai video of the new generation: artificial intelligence turns text into stylish and realistic pictures and videos.

Discover Savin Kuk, a picturesque corner of Montenegro. Skiing, hiking, panoramic views and the cleanest air. A great choice for a relaxing and active holiday.

Срочные микрозаймы https://stuff-money.ru с моментальным одобрением. Заполните заявку онлайн и получите деньги на карту уже сегодня. Надёжно, быстро, без лишней бюрократии.

Срочный микрозайм https://truckers-money.ru круглосуточно: оформите онлайн и получите деньги на карту за считаные минуты. Без звонков, без залога, без лишних вопросов.

¡Saludos, participantes de retos !

Casino sin licencia con seguridad avanzada – п»їaudio-factory.es casino online sin licencia espaГ±a

¡Que disfrutes de asombrosas momentos irrepetibles !

Этот бот способен найти данные по заданному профилю.

Укажите имя, фамилию , чтобы получить сведения .

Система анализирует публичные данные и цифровые следы.

глаз бога найти телефон

Результаты формируются мгновенно с проверкой достоверности .

Идеально подходит для анализа профилей перед важными решениями.

Анонимность и актуальность информации — наш приоритет .

Your means of telling everything in this paragraph is

truly pleasant, all be able to simply be aware of it, Thanks

a lot.

My page :: Eharmony Special Coupon Code 2025

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Этот бот поможет получить данные по заданному профилю.

Укажите имя, фамилию , чтобы сформировать отчёт.

Система анализирует публичные данные и цифровые следы.

bot глаз бога

Информация обновляется в реальном времени с фильтрацией мусора.

Оптимален для проверки партнёров перед сотрудничеством .

Конфиденциальность и точность данных — наш приоритет .

металлический значок пин металлические пины значки

Коллекция Nautilus, созданная мастером дизайна Жеральдом Гентой, сочетает элегантность и высокое часовое мастерство. Модель Nautilus 5711 с самозаводящимся механизмом имеет 45-часовой запас хода и корпус из нержавеющей стали.

Восьмиугольный безель с округлыми гранями и синий солнечный циферблат подчеркивают уникальность модели. Браслет с интегрированными звеньями обеспечивает удобную посадку даже при активном образе жизни.

Часы оснащены индикацией числа в позиции 3 часа и сапфировым стеклом.

Для сложных модификаций доступны хронограф, вечный календарь и индикация второго часового пояса.

Приобрести часы Патек Филип Nautilus на этом сайте

Например, модель 5712/1R-001 из красного золота 18K с механизмом на 265 деталей и запасом хода на двое суток.

Nautilus остается символом статуса, объединяя инновации и классические принципы.

производство металлических значков металлические значки

типография сайт типография спб дешево

типография петербург типография спб

нужен юрист консультант задать вопрос для бесплатной помощи адвоката юриста

¡Hola, seguidores del entretenimiento !

Casino sin licencia con juegos de casino en vivo – п»їhttps://casinosinlicenciaespana.xyz/ casinos online sin licencia

¡Que vivas increíbles instantes únicos !

пансионат для пожилых адрес частный пансионат для пожилых

наркология клиника наркология клиника

1С без сложностей https://1s-legko.ru объясняем простыми словами. Как работать в программах 1С, решать типовые задачи, настраивать учёт и избегать ошибок.

Онлайн-тренинги https://communication-school.ru и курсы для личного роста, карьеры и новых навыков. Учитесь в удобное время из любой точки мира.

Перевод документов https://medicaltranslate.ru на немецкий язык для лечения за границей и с немецкого после лечения: высокая скорость, безупречность, 24/7

Хотите собрать данные о человеке ? Этот бот поможет детальный отчет в режиме реального времени .

Используйте продвинутые инструменты для анализа публичных записей в открытых источниках.

Выясните место работы или интересы через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

бот глаз бога телеграмм

Система функционирует с соблюдением GDPR, обрабатывая общедоступную информацию.

Получите расширенный отчет с историей аккаунтов и списком связей.

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для digital-расследований — результаты вас удивят !

Наш сервис способен найти информацию о любом человеке .

Укажите никнейм в соцсетях, чтобы сформировать отчёт.

Система анализирует открытые источники и активность в сети .

глаз бога телега

Информация обновляется мгновенно с проверкой достоверности .

Идеально подходит для анализа профилей перед сотрудничеством .

Анонимность и актуальность информации — наш приоритет .

Нужно собрать данные о человеке ? Наш сервис предоставит полный профиль в режиме реального времени .

Воспользуйтесь продвинутые инструменты для поиска публичных записей в открытых источниках.

Узнайте место работы или интересы через автоматизированный скан с верификацией результатов.

глаз бога в телеграме

Система функционирует с соблюдением GDPR, обрабатывая общедоступную информацию.

Закажите детализированную выжимку с геолокационными метками и списком связей.

Попробуйте проверенному решению для digital-расследований — результаты вас удивят !

Hello keepers of pristine spaces !

Air Purifiers for Smoke – Best Quiet Models – http://bestairpurifierforcigarettesmoke.guru best air filter for smoke

May you experience remarkable refined serenity !

Репетитор по физике https://repetitor-po-fizike-spb.ru СПб: школьникам и студентам, с нуля и для олимпиад. Четкие объяснения, практика, реальные результаты.

?Hola, descubridores de oportunidades unicas!

casino fuera de EspaГ±a disponible las 24 horas – https://www.casinosonlinefueradeespanol.xyz/# casinosonlinefueradeespanol

?Que disfrutes de asombrosas conquistas impresionantes !

Mostbet Aviator Azərbaycan Necə Pul Qazanmalı Read More » Fot. MarcinMaczuga Hello forum members! I am currently interested in gambling and really want to find something really worthwhile to earn money. I am new to gambling and probably a game with simple gameplay without any serious knowledge would suit me. What game would you recommend me? Thanks in advance! Płatności Revolut 2023 Lista Najlepszych Kasyn RevolutJak Dokonać Wpłaty W Vulkanbet I Wypłacić PieniędzyContentVulkan Vegas — Wypłaty W KasynieNajnowsze Bonusy Bez Depozytu 2023! Dlaczego Warto Skorzystać Z Bonusu Bez Depozytu? Rodzaje Gier, W Jakie Można Zagrać T KasynieHotslots Casino – 40 Darmowych Spinów Za Rejestrację Mhh Slot Sugar RushW Jakich Automatach Mogę Wykorzystać Bonus Bez Depozytu? Warunki We Zasady — Bonus Bez DepozytuJakie Metody Płatności Dostępne Są Dla Graczy Z Polski? Prezentujemy Najlepsze Bonusy W Vulkan VegasProces Wypłaty Pieniędzy Z…

https://old.datahub.io/es/user/clansefacjoy1976

Mostbet, Azərbaycanda Ən Yaxşı Onlayn Kazinolardan Biri Rəsmi Sayt, Güzgü Və Bonuslar Content Lisenziyalı Kazino Və Idman Mərcləri Mostbet Kazino Tətbiqi Mostbet Kazino Oyunları Seçimləri Mostbet-də Populyar Kazino Oyunları Mostbet Odbierz W Vulkan Vegas Darmowy Bonus Za RejestracjęVulkan Vegas Bonus Za Rejestrację Odbierz Darmowy BonusContentCzy W Promocji Na Darmowe Pieniądze Wymagany Jest Specjalny Vulkan Vegas Kod Promocyjny, Aby Aktywować Ofertę?Gdzie Można Zdobyć 25 Euro Bez Depozytu?Bonus Bez Depozytu W Kasynie ScattersKasyno Na Żywo Z Krupierem W ScattersJak Działa Vulkan Vegas No Deposit Bonus?Bonus Za Rejestrację Na Stronie Vulkan VegasJak Aktywować Vulkan Vegas 25 Euro Bez Depozytu?Dostawcy Gier 25 Euro Bez DepozytuJak Wypłacić Nagrodę Z 25€ No Deposit Bonus?Vulkan Vegas Bonus 25…

¡Saludos, cazadores de premios únicos!

Casinoextranjerosdeespana.es – Juegos desde tu paГs – https://www.casinoextranjerosdeespana.es/# casino online extranjero

¡Que experimentes maravillosas momentos irrepetibles !

Украинский бизнес https://in-ukraine.biz.ua информацинный портал о бизнесе, финансах, налогах, своем деле в Украине

Сплит-система купить https://brand-climat.ru современные модели с тихой работой и инверторным управлением. Подбор под ваши задачи, быстрая доставка и официальная гарантия. Идеальное решение для дома и офиса!

Быстрый ремонт бытовой техники на дому без очередей.

Женский блог https://zhinka.in.ua Жінка это самое интересное о красоте, здоровье, отношениях. Много полезной информации для женщин.

¡Bienvenidos, usuarios de sitios de azar !

casinofueraespanol con interfaz intuitiva y moderna – п»їhttps://casinofueraespanol.xyz/ п»їп»їcasino fuera de espaГ±a

¡Que vivas increíbles recompensas fascinantes !

Сайт Житомир https://u-misti.zhitomir.ua новости и происшествия в Житомире и области

Современные механические часы сочетают вековые традиции с инновационными сплавами, такими как титан и сапфировое стекло.

Прозрачные задние крышки из сапфирового кристалла позволяют любоваться калибром в действии.

Маркировка с Super-LumiNova обеспечивает яркую подсветку, сохраняя эстетику циферблата.

https://sites.google.com/view/royaloak14790

Модели вроде Rolex Day-Date дополняют хронографами и вечными календарями.

Часы с роторным механизмом не требуют батареек, преобразуя движение руки в энергию для работы.

Luxury mechanical watches combine artisanal precision with modern innovation, offering sophisticated design through automatic mechanisms that harness kinetic energy.

From intricate skeleton dials to hand-polished tourbillons, these timepieces showcase technical artistry in materials like 18k rose gold and sapphire crystal.

Brands like Rolex and Patek Philippe craft iconic collections with extended autonomy and dive-ready durability, merging functionality with exclusivity.

https://bundas24.com/read-blog/140091

Unlike quartz alternatives, mechanical watches require no batteries, relying on manual winding or rotor systems to deliver reliable timekeeping.

Explore vintage-inspired designs at retailers like CHRONEXT, where new luxury watches from top maisons are available with certified authenticity.

Клининг в Москве становится все более популярным. Из-за напряженного ритма жизни в Москве многие люди обращаются к профессионалам для уборки.

Клиниговые фирмы предлагают целый ряд услуг в области уборки. Профессиональный клининг включает как стандартную уборку, так и глубокую очистку в зависимости от потребностей клиентов.

При выборе клининговой компании важно обратить внимание на опыт работы и отзывы клиентов. Профессиональный подход и соблюдение чистоты и порядка важно для обеспечения высокого качества услуг.

Итак, обращение к услугам клининговых компаний в Москве помогает упростить жизнь занятых горожан. Каждый может выбрать подходящую компанию, чтобы обеспечить себе чистоту и порядок в доме.

клининговая компания москва http://www.uborkaklining1.ru/ .

займ онлайн с плохой https://zajmy-onlajn.ru

стоимость отчета по практике написание отчета по практике на заказ

сделать диплом заказ дипломной работы

купить контрольную по истории сделать контрольную на заказ

Портал Киева https://u-misti.kyiv.ua новости и события в Киеве сегодня.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

¡Hola, buscadores de tesoros ocultos !

casinosextranjerosdeespana.es – apuestas personalizadas – https://www.casinosextranjerosdeespana.es/ casinos extranjeros

¡Que vivas increíbles instantes únicos !

контрольные под заказ https://kontrolnyestatistika.ru/

¡Saludos, amantes de la emoción !

casinos por fuera accesibles desde navegador – https://www.casinosonlinefueraespanol.xyz/# casino por fuera

¡Que disfrutes de instantes inolvidables !

Автогид https://avtogid.in.ua автомобильный украинский портал с новостями, обзорами, советами для автовладельцев

лучшие микрозаймы zajmy-onlajn.ru/

Файне Винница https://faine-misto.vinnica.ua новости и события Винницы сегодня. Городской портал, обзоры.

ただし、保険会社による被害者との直接折衝については、非弁行為を禁止した弁護士法第72条に抵触する可能性があり、この権利の行使は慎重な判断が求められる。第4話(四杯目)は『全日本フィギュアスケート選手権』男子シングルショートプログラムの放送時間5分延長(フジテレビ制作、19:00 – 21:05)のため、5分繰り下げ(23:45 – 0:40)。尚、第一生命とは融資・兵庫県宝塚市出生、埼玉県志木市出身。神奈川県横浜市出身。

На данном сайте можно получить мессенджер-бот “Глаз Бога”, который найти данные о человеке через открытые базы.

Бот активно ищет по ФИО, используя актуальные базы онлайн. Благодаря ему можно получить бесплатный поиск и глубокий сбор по имени.

Сервис проверен согласно последним данным и включает фото и видео. Глаз Бога гарантирует найти профили в соцсетях и покажет сведения в режиме реального времени.

глаз бога телефон

Данный инструмент — выбор для проверки персон онлайн.

Медпортал https://medportal.co.ua украинский блог о медициние и здоровье. Новости, статьи, медицинские учреждения

где заказать дипломную работу заказать дипломная работа

купить реферат цена https://referatymehanika.ru

отчет по практике на заказ отчет по практике сколько стоит

Монтаж оборудования для наблюдения поможет защиту помещения в режиме 24/7.

Продвинутые системы обеспечивают высокое качество изображения даже в темное время суток.

Наша компания предоставляет множество решений устройств, идеальных для дома.

videonablyudeniemoskva.ru

Грамотная настройка и техническая поддержка обеспечивают эффективным и комфортным для всех заказчиков.

Свяжитесь с нами, для получения оптимальное предложение по внедрению систем.

Хмельницький новини https://u-misti.khmelnytskyi.ua огляди, новини, сайт Хмельницького

¡Bienvenidos, seguidores de la adrenalina !

Casino fuera de EspaГ±a con conexiГіn segura – https://www.casinoporfuera.guru/ casinoporfuera

¡Que disfrutes de maravillosas premios asombrosos !

На данном сайте доступен Telegram-бот “Глаз Бога”, что найти всю информацию о человеке из открытых источников.

Инструмент активно ищет по фото, анализируя публичные материалы онлайн. С его помощью осуществляется бесплатный поиск и глубокий сбор по фото.

Сервис обновлен на 2025 год и включает мультимедийные данные. Сервис гарантирует узнать данные в соцсетях и предоставит информацию за секунды.

программа глаз бога для поиска людей

Данный инструмент — выбор при поиске людей через Telegram.

Klavier noten piano klavier noten

Взять займ в интернете микрозайм взять

Офисная мебель https://officepro54.ru в Новосибирске купить недорого от производителя

защитный кейс альфа plastcase

Женский портал https://woman24.kyiv.ua обо всём, что волнует: красота, мода, отношения, здоровье, дети, карьера и вдохновение.

Только главное https://ua-vestnik.com о событиях в Украине: свежие сводки, аналитика, мнения, происшествия и реформы.

¡Hola, participantes del juego !

casinoextranjero.es – apuestas seguras y sin censura – https://www.casinoextranjero.es/ casino online extranjero

¡Que vivas oportunidades irrepetibles !

Мировые новости https://ua-novosti.info онлайн: политика, экономика, конфликты, наука, технологии и культура.

Портал для женщин https://a-k-b.com.ua любого возраста: стиль, красота, дом, психология, материнство и карьера.

Онлайн-новости https://arguments.kyiv.ua без лишнего: коротко, по делу, достоверно. Политика, бизнес, происшествия, спорт, лайфстайл.

Информационный портал https://dailynews.kyiv.ua актуальные новости, аналитика, интервью и спецтемы.

Новостной портал https://news24.in.ua нового поколения: честная журналистика, удобный формат, быстрый доступ к ключевым событиям.

Городской портал Одессы https://faine-misto.od.ua последние новости и происшествия в городе и области

На данном сайте вы найдете мессенджер-бот “Глаз Бога”, позволяющий проверить всю информацию о человеке по публичным данным.

Инструмент функционирует по номеру телефона, обрабатывая актуальные базы в сети. Благодаря ему можно получить пять пробивов и глубокий сбор по имени.

Инструмент проверен на август 2024 и охватывает аудио-материалы. Глаз Бога поможет проверить личность в соцсетях и отобразит результаты мгновенно.

глаз бога программа для поиска людей бесплатно

Данный бот — помощник для проверки персон удаленно.

Новостной портал Одесса https://u-misti.odesa.ua последние события города и области. Обзоры и много интресного о жизни в Одессе.

Портал о строительстве https://tozak.org.ua от идеи до готового дома. Проекты, сметы, выбор материалов, ошибки и их решения.

Строительный журнал https://dsmu.com.ua идеи, технологии, материалы, дизайн, проекты, советы и обзоры. Всё о строительстве, ремонте и интерьере

Всё об автомобилях https://autoclub.kyiv.ua в одном месте. Обзоры, новости, инструкции по уходу, автоистории и реальные тесты.

Новости Украины https://hansaray.org.ua 24/7: всё о жизни страны — от региональных происшествий до решений на уровне власти.

Всё о строительстве https://ukrainianpages.com.ua просто и по делу. Портал с актуальными статьями, схемами, проектами, рекомендациями специалистов.

Архитектурный портал https://skol.if.ua современные проекты, урбанистика, дизайн, планировка, интервью с архитекторами и тренды отрасли.

Информационный портал https://comart.com.ua о строительстве и ремонте: полезные советы, технологии, идеи, лайфхаки, расчёты и выбор материалов.

Новости Украины https://useti.org.ua в реальном времени. Всё важное — от официальных заявлений до мнений экспертов.

События Днепр https://u-misti.dp.ua последние новости Днепра и области, обзоры и самое интересное

Всё о спорте https://beachsoccer.com.ua в одном месте: профессиональный и любительский спорт, фитнес, здоровье, техника упражнений и спортивное питание.

Туристический портал https://aliana.com.ua с лучшими маршрутами, подборками стран, бюджетными решениями, гидами и советами.

Клуб родителей https://entertainment.com.ua пространство поддержки, общения и обмена опытом.

Семейный портал https://stepandstep.com.ua статьи для родителей, игры и развивающие материалы для детей, советы психологов, лайфхаки.

¡Saludos, fanáticos del azar !

Lo nuevo en casino online extranjero este mes – п»їhttps://casinoextranjerosenespana.es/ casinoextranjerosenespana.es

¡Que disfrutes de conquistas memorables !

Портал о маркетинге https://reklamspilka.org.ua рекламе и PR: свежие идеи, рабочие инструменты, успешные кейсы, интервью с экспертами.

Современный женский https://prowoman.kyiv.ua портал: полезные статьи, лайфхаки, вдохновляющие истории, мода, здоровье, дети и дом.

Онлайн-портал https://leif.com.ua для женщин: мода, психология, рецепты, карьера, дети и любовь. Читай, вдохновляйся, общайся, развивайся!

Новини Львів https://faine-misto.lviv.ua последние новости и события – Файне Львов

Комплексный строительный https://ko-online.com.ua портал: свежие статьи, советы, проекты, интерьер, ремонт, законодательство.

Всё о строительстве https://furbero.com в одном месте: новости отрасли, технологии, пошаговые руководства, интерьерные решения и ландшафтный дизайн.

Строительный портал https://apis-togo.org полезные статьи, обзоры материалов, инструкции по ремонту, дизайн-проекты и советы мастеров.

Авто портал https://real-voice.info для всех, кто за рулём: свежие автоновости, обзоры моделей, тест-драйвы, советы по выбору, страхованию и ремонту.

Сайт о строительстве https://solution-ltd.com.ua и дизайне: как построить, отремонтировать и оформить дом со вкусом.

Свежие новости https://ktm.org.ua Украины и мира: политика, экономика, происшествия, культура, спорт. Оперативно, объективно, без фейков.

Портал Львів https://u-misti.lviv.ua останні новини Львова и области.

¡Saludos, apostadores entusiastas !

Juegos exclusivos en casinos online extranjeros – https://www.casinosextranjero.es/# mejores casinos online extranjeros

¡Que vivas increíbles jugadas excepcionales !

Городской портал Винницы https://u-misti.vinnica.ua новости, события и обзоры Винницы и области

¡Hola, jugadores apasionados !

Casino sin licencia con pago automatizado – http://www.casinossinlicenciaespana.es/ casino sin registro

¡Que experimentes conquistas extraordinarias !

Сайт о строительстве https://selma.com.ua практические советы, современные технологии, пошаговые инструкции, выбор материалов и обзоры техники.

Ремонт без стресса https://odessajs.org.ua вместе с нами! Полезные статьи, лайфхаки, дизайн-проекты, калькуляторы и обзоры.

Портал о ремонте https://as-el.com.ua и строительстве: от черновых работ до отделки. Статьи, обзоры, идеи, лайфхаки.

Все новинки https://helikon.com.ua технологий в одном месте: гаджеты, AI, робототехника, электромобили, мобильные устройства, инновации в науке и IT.

ИнфоКиев https://infosite.kyiv.ua события, новости обзоры в Киеве и области.

¡Hola, jugadores apasionados !

CГіmo registrarte en un casino fuera de EspaГ±a legalmente – https://casinoonlinefueradeespanol.xyz/# casinos fuera de espaГ±a

¡Que disfrutes de asombrosas premios extraordinarios !

Читайте мужской https://zlochinec.kyiv.ua журнал онлайн: тренды, обзоры, советы по саморазвитию, фитнесу, моде и отношениям. Всё о том, как быть уверенным, успешным и сильным — каждый день.

Журнал для мужчин https://swiss-watches.com.ua которые ценят успех, свободу и стиль. Практичные советы, мотивация, интервью, спорт, отношения, технологии.

Мужской журнал https://hand-spin.com.ua о стиле, спорте, отношениях, здоровье, технике и бизнесе. Актуальные статьи, советы экспертов, обзоры и мужской взгляд на важные темы.

Кулинарный портал https://vagon-restoran.kiev.ua с тысячами проверенных рецептов на каждый день и для особых случаев. Пошаговые инструкции, фото, видео, советы шефов.

Новости Полтава https://u-misti.poltava.ua городской портал, последние события Полтавы и области

Полезный сайт https://vasha-opora.com.ua для тех, кто строит: от фундамента до крыши. Советы, инструкции, сравнение материалов, идеи для ремонта и дизайна.

Журнал о строительстве https://sovetik.in.ua качественный контент для тех, кто строит, проектирует или ремонтирует. Новые технологии, анализ рынка, обзоры материалов и оборудование — всё в одном месте.

Строительный журнал https://poradnik.com.ua для профессионалов и частных застройщиков: новости отрасли, обзоры технологий, интервью с экспертами, полезные советы.

Всё о строительстве https://stroyportal.kyiv.ua в одном месте: технологии, материалы, пошаговые инструкции, лайфхаки, обзоры, советы экспертов.

Новинний сайт Житомира https://faine-misto.zt.ua новости Житомира сегодня

Znając różnice między nimi jest bardzo ważne dla Ciebie gracz, który wynosi sześć. Dzięki temu firma zasługuje na idealne 5 na 5, heres kasyno online. Aby grać za darmo, bez którego nie ma ani jednego gospodarstwa z żadnym Chińskim świętem narodowym. Na szczęście istnieje wiele innych bezpiecznych metod płatności, popularne gry w kasynie a także inne dane w HUD-ach. Jeszcze lepiej, które mogą wylądować jako pojedyncze. Aby wypłacić wygrane z gier kasynowych, postępuj zgodnie z poniższą instrukcją: Spēlētāji var palaist Aviator demo Vavada, bet šajā režīmā jūs nevarat iegūt reālus laimestus. Lai spēlētu ar īstu money, jums ir jāpapildina savs Casino konts, izmantojot vienu no pieejamajām metodēm:

https://freesocialbookmarkingsites.xyz/page/business-services/tutaj

PIN-UP.UA to legalne kasyno online, które otrzymało licencję od KRIL w 2021 roku (nr 147 z dnia 9 kwietnia 2021 roku) na okres 5 lat. To kasyno jest prowadzone przez LLC “UKR GAME TECHNOLOGY”. Oficjalna, autonomiczna Aviator Game App (od Spribe) bywa rzadziej spotykana, częściej gracze korzystają z aplikacji konkretnego kasyna, w której Aviator jest jedną z pozycji w portfolio. Jeżeli operator oferuje natywną aplikację na iOS czy Android, zazwyczaj można pobrać ją bezpośrednio z oficjalnej strony (jeśli jest to możliwe w Twoim kraju) lub ze sklepu Apple App Store Google Play, jeśli przepisy lokalne na to zezwalają. Copyright © 2014-2025 APKPure. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone. By admin|2025-01-24T00:26:14+00:00January 24th, 2025|Игра Авиатор Aviator Online Ru Как Работает – 332|

Информационный журнал https://newhouse.kyiv.ua для строителей: строительные технологии, материалы, тенденции, правовые аспекты.

Современный строительный https://interiordesign.kyiv.ua журнал: идеи, решения, технологии, тенденции. Всё о ремонте, стройке, дизайне и инженерных системах.

Онлайн-журнал https://inox.com.ua о строительстве: обзоры новинок, аналитика, советы, интервью с архитекторами и застройщиками.

Строительный журнал https://garant-jitlo.com.ua всё о технологиях, материалах, архитектуре, ремонте и дизайне. Интервью с экспертами, кейсы, тренды рынка.

¡Saludos, entusiastas del riesgo !

Casino online extranjero con cashback semanal – https://www.casinosextranjerosenespana.es/ casinosextranjerosenespana.es

¡Que vivas increíbles victorias épicas !

Всё для строительства https://d20.com.ua и ремонта: инструкции, обзоры, экспертизы, калькуляторы. Профессиональные советы, новинки рынка, база строительных компаний.

центр лечения наркомании https://narco-info.ru

заказать оценку Москва экспертная оценка ооо

Праздничная продукция https://prazdnik-x.ru для любого повода: шары, гирлянды, декор, упаковка, сувениры. Всё для дня рождения, свадьбы, выпускного и корпоративов.

безопасный вывод из запоя цены вывод из запоя в наркологической клинике в нижнем новгороде

лечение алкоголизма https://alko-info.ru

кодировка от алкоголизма в нижнем кодировка торпедой от алкоголя

нарколог на дом недорого вызвать нарколога на дом анонимно

Портал города Черновцы https://u-misti.chernivtsi.ua последние новости, события, обзоры

Коллекция Nautilus, созданная мастером дизайна Жеральдом Гентой, сочетает элегантность и прекрасное ремесленничество. Модель Nautilus 5711 с автоматическим калибром 324 SC имеет 45-часовой запас хода и корпус из нержавеющей стали.

Восьмиугольный безель с округлыми гранями и синий солнечный циферблат подчеркивают уникальность модели. Браслет с H-образными элементами обеспечивает комфорт даже при активном образе жизни.

Часы оснащены индикацией числа в позиции 3 часа и сапфировым стеклом.

Для версий с усложнениями доступны секундомер, вечный календарь и индикация второго часового пояса.

Найти часы Филипп Наутилус оригинал

Например, модель 5712/1R-001 из красного золота 18K с калибром повышенной сложности и запасом хода на двое суток.

Nautilus остается предметом коллекционирования, объединяя современные технологии и классические принципы.

Городской портал Черкассы https://u-misti.cherkasy.ua новости, обзоры, события Черкасс и области

Строительный портал https://proektsam.kyiv.ua свежие новости отрасли, профессиональные советы, обзоры материалов и технологий, база подрядчиков и поставщиков. Всё о ремонте, строительстве и дизайне в одном месте.

¡Hola, exploradores de oportunidades !

Casinoextranjerosespana.es: lista de casinos sin documentos – https://www.casinoextranjerosespana.es/# п»їcasinos online extranjeros

¡Que disfrutes de asombrosas momentos memorables !

онлайн займы на карту без отказа мфо займы онлайн

Эта платформа собирает свежие информационные статьи со всего мира.

Здесь можно найти события из жизни, бизнесе и многом другом.

Материалы выходят регулярно, что позволяет держать руку на пульсе.

Минималистичный дизайн ускоряет поиск.

https://julistyle.ru

Все публикации оформлены качественно.

Целью сайта является достоверности.

Оставайтесь с нами, чтобы быть на волне новостей.

Au début, vous disposez d’un pack de personnages de départ, qui comprend certains des principaux guerriers de Naruto. Ensuite, vous pouvez en obtenir d’autres et débloquer de nouvelles récompenses à chaque niveau passé. Prénom* Of course a job like that would have cost a lot of money. Not by outside standards, no. Prison economics are on a smaller scale. When you’ve been in here awhile, a dollar bill in your hand looks like a twenty did outside. My guess is that, if Bogs was done, it cost someone a serious piece of change—fifteen bucks, we’ll say, for the turnkey, and two or three apiece for each of the lump-up guys. Androidsis » Applications Android Prénom* Désolé, ce produit n’est pas disponible. Veuillez choisir une combinaison différente. Désolé, ce produit n’est pas disponible. Veuillez choisir une combinaison différente.

https://masmatarpufn1975.tearosediner.net/cliquez-ici

Pour les passionnés de football, nous comprenons la passion et l’excitation du sport. Et lorsque Evoplay Entertainment a lancé le jeu de machine à sous Penalty Shoot Out, il est devenu évident qu’ils ont touché le cœur des fans partout. Ici, nous explorerons ce jeu instantané qui défie les conventions traditionnelles des machines à sous et offre une expérience interactive. 0613753863 Ci-dessous, vous retrouverez un tableau récapitulatif des gains sur Penalty Shoot Out Street. Chaque année, de nouveaux mini-jeux apparaissent, comme Penalty Shoot Out Street lancé par Evoplay en 2023. Ce mini-jeu à la thématique footballistique est un des plus excitants du moment et il est possible d’y jouer sur une multitude de casinos en ligne. Dans cet article, nous vous expliquons comment faire des dépôts pour jouer à ce jeu et comment encaisser vos gains.

¡Saludos, descubridores de tesoros !

Un casino online extranjero suele incluir rankings semanales donde compites con otros jugadores por premios especiales. casinos extranjeros Esto aГ±ade motivaciГіn adicional. Jugar se convierte en una competiciГіn sana.

Explora nuevas opciones en mejores casinos online extranjeros – п»їhttps://casinosextranjerosespana.es/

Un casino online extranjero puede incluir funciones de realidad virtual para explorar salas en 360В°. La inmersiГіn es total. Como estar en Las Vegas, pero desde casa.

¡Que experimentes increíbles instantes inolvidables !

Семейный юрист yuristy-ekaterinburga.ru/

Ce modèle Jumbo arbore un boîtier en acier inoxydable ultra-mince (8,1 mm d’épaisseur), équipé du nouveau mouvement Manufacture 7121 offrant une autonomie étendue.

Le cadran « Bleu Nuit Nuage 50 » présente un motif Petite Tapisserie associé à des chiffres luminescents et des aiguilles Royal Oak.

Une glace saphir anti-reflets garantit une lisibilité optimale.

Montres de luxe Piguet Royal Oak 14790st – caractéristiques

Outre l’heure traditionnelle, la montre intègre une indication pratique du jour. Étanche à 50 mètres, elle résiste aux éclaboussures et plongées légères.

Le maille milanaise ajustable et la carrure à 8 vis reprennent les codes du design signé Gérald Genta (1972). Un boucle personnalisée assure un maintien parfait.

Appartenant à la série Jumbo historique, ce garde-temps allie savoir-faire artisanal et élégance discrète, avec un prix estimé à ~70 000 €.

¡Bienvenidos, entusiastas del ocio !

Muchos casinos online extranjeros actualizan sus bonos cada semana para mantener el interГ©s.

ВїSon seguros los casinos extranjeros para apostar desde EspaГ±a? – https://www.casinoextranjeros.es/

Elegir casinos extranjeros te permite jugar sin lГmites impuestos por regulaciones nacionales. Estas plataformas suelen aceptar jugadores desde mГєltiples paГses sin necesidad de verificaciГіn rigurosa. Su catГЎlogo de juegos tambiГ©n es mГЎs amplio y con mayor variedad temГЎtica.

¡Que vivas asombrosas tiradas exitosas !

¡Saludos, jugadores profesionales !

Los casinos sin licencia EspaГ±a no aplican restricciones en las cantidades mГЎximas de depГіsito. TГє decides cuГЎnto y cuГЎndo jugar. Sin lГmites absurdos que interrumpan tu sesiГіn.

Las sumas acumuladas pueden cambiar la vida de cualquier jugador.

GuГa completa de casinos sin licencia para jugadores en EspaГ±a – http://www.casinos-sinlicenciaenespana.es/

¡Que disfrutes de conquistas destacadas !

Sweet blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Appreciate it

КредитоФФ http://creditoroff.ru удобный онлайн-сервис для подбора и оформления займов в надёжных микрофинансовых организациях России. Здесь вы найдёте лучшие предложения от МФО

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

¡Saludos, apasionados del ocio !

AsГ no te pierdes ninguna oportunidad. La personalizaciГіn es clave.

ВїSon seguros los casinos online extranjeros? – п»їhttps://casinos-extranjeros.es/

Algunos casinos extranjeros permiten el acceso desde paГses bloqueados usando tecnologГa anti-GEO restrictiva. AsГ puedes seguir jugando estГ©s donde estГ©s. Sin fronteras reales.

¡Que disfrutes de increíbles oportunidades irrepetibles !

Die Royal Oak 16202ST kombiniert ein 39-mm-Edelstahlgehäuse mit einem extraflachen Gehäuse von nur 8,1 mm Dicke.

Ihr Herzstück bildet das automatische Manufakturwerk 7121 mit 55 Stunden Gangreserve.

Der smaragdene Farbverlauf des Zifferblatts wird durch das feine Guillochierungen und die Saphirglas-Abdeckung mit blendschutzbeschichteter Oberfläche betont.

Neben Stunden- und Minutenanzeige bietet die Uhr ein praktisches Datum bei Position 3.

Audemars Royal Oak 15407st uhr

Die bis 5 ATM geschützte Konstruktion macht sie alltagstauglich.

Das integrierte Edelstahlarmband mit faltsicherer Verschluss und die achtseitige Rahmenform zitieren das ikonische Royal-Oak-Erbe aus den 1970er Jahren.

Als Teil der „Jumbo“-Kollektion verkörpert die 16202ST horlogerie-Tradition mit einem Wertanlage für Sammler.

ultimate AI porn maker generator. Create hentai art, porn comics, and NSFW with the best AI porn maker online. Start generating AI porn now!

консультация медицинского юриста срочная консультация юриста по телефону бесплатно

Launched in 1999, Richard Mille revolutionized luxury watchmaking with cutting-edge innovation . The brand’s iconic timepieces combine aerospace-grade ceramics and sapphire to balance durability .

Mirroring the aerodynamics of Formula 1, each watch prioritizes functionality , optimizing resistance. Collections like the RM 011 Flyback Chronograph redefined horological standards since their debut.

Richard Mille’s collaborations with experts in mechanical engineering yield skeletonized movements crafted for elite athletes.

True Mille Richard RM6501 models

Rooted in innovation, the brand pushes boundaries through bespoke complications for collectors .

With a legacy , Richard Mille remains synonymous with modern haute horlogerie, appealing to global trendsetters.

The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, revolutionized luxury watchmaking with its signature angular case and stainless steel craftsmanship .

Ranging from limited-edition sand gold to diamond-set variants, the collection combines avant-garde design with horological mastery.

Priced from $20,000 to over $400,000, these timepieces attract both luxury enthusiasts and aficionados seeking investable art .

Original AP Royal Oak 26240 or information

The Perpetual Calendar models push boundaries with robust case constructions, embodying Audemars Piguet’s technical prowess .

Thanks to meticulous hand-finishing , each watch epitomizes the brand’s legacy of craftsmanship.

Explore exclusive releases and historical insights to elevate your collection with this timeless icon .

Discover the iconic Patek Philippe Nautilus, a luxury timepiece that blends sporty elegance with refined artistry.

Introduced nearly 50 years ago, this legendary watch revolutionized high-end sports watches, featuring distinctive octagonal bezels and textured sunburst faces.

For stainless steel variants like the 5990/1A-011 with a 55-hour energy retention to luxurious white gold editions such as the 5811/1G-001 with a blue gradient dial , the Nautilus caters to both avid enthusiasts and everyday wearers .

Unworn Philippe Nautilus 5980r timepieces

Certain diamond-adorned versions elevate the design with dazzling bezels , adding unparalleled luxury to the timeless profile.

With market values like the 5726/1A-014 at ~$106,000, the Nautilus remains a coveted investment in the world of premium watchmaking.

Whether you seek a historical model or contemporary iteration , the Nautilus epitomizes Patek Philippe’s tradition of innovation.

Профессиональное https://kosmetologicheskoe-oborudovanie-msk.ru для салонов красоты, клиник и частных мастеров. Аппараты для чистки, омоложения, лазерной эпиляции, лифтинга и ухода за кожей.

купить плитку 600х1200 купить плитку керамогранит

I used to be able to find good information from your content.

¡Hola, entusiastas de los juegos !

Un casino fuera de espaГ±a no impone condiciones de uso tan estrictas como los operadores locales.Puedes jugar sin miedo a bloqueos injustificados.Las reglas estГЎn explicadas claramente.

casino por fuera

Casino fuera de espaГ±a con juegos exclusivos para mГіviles – п»їhttps://casinoporfuera.xyz/

¡Que disfrutes de logros impresionantes

Mas talvez seja mais barato que comprar um LIFT e reprojetá-lo para ser um substituto da FAB. The Mitsubishi X-2 Shinshin is intended to be a stealth jet fighter. While the F-35 is a new jet, it is American-made, and some reports have indicated that Japan would like its own model so as not to rely on foreign imports to cover that military need. Setor aeroespacial pressiona governo Trump contra novas tarifas Este produto não está disponível no teu idioma local. Verifica a lista de idiomas disponíveis antes de fazeres a compra. Este produto não está disponível no teu idioma local. Verifica a lista de idiomas disponíveis antes de fazeres a compra. Bocal de empuxo vetorial do turbofan WS-15 aprimorado, em imagem capturada de vídeo O terceiro lote de turbofans WS-15 da… To-201 Shikra – The To-201 Shikra is a fifth-generation, single-seat, twin-engine, all-weather tactical fighter jet. The aircraft was designed by a CSAT and Russian joint syndicate with the goal to build a highly agile and maneuverable air-superiority fighter. Similar to the F A-181, the To-201 also has ground attack capabilities, and is able to support various weapons configurations via its conventional pylons, but also its internal weapons bay.

https://bigchangeedu.com/plinko-da-bgaming-analise-geografica-do-jogo-de-cassino-online-no-brasil/

O Lucky Jet facilita a gestão de suas finanças. Tudo o que você precisa é de uma conta online, e você pode fazer depósitos e saques com apenas alguns cliques. Os jogadores não precisam se preocupar com longos tempos de espera ou taxas ocultas. A Lucky Jet oferece vários métodos de pagamento confiáveis, incluindo cartões de débito crédito Visa, Skrill, Neteller, Trust. Lucky Jet também tem uma aplicação móvel, permitindo que você jogue em qualquer lugar e a qualquer hora. Baixe o aplicativo da loja de aplicativos do seu smartphone ou tablet e prepare-se para uma experiência inesquecível. Com o aplicativo, você pode facilmente gerenciar suas finanças, jogar em diferentes versões do Lucky Jet, solicitar ofertas de bônus e muito mais! Portanto, não espere – baixe o aplicativo Lucky Jet hoje mesmo e comece a jogar!

Алкоголь с доставкой прямо к двери — просто оформите заказ онлайн

заказать алкоголь на дом алкоторг доставка алкоголя москва .

ship a car automobile transport services

Сертификация и лицензии — ключевой аспект ведения бизнеса в России, гарантирующий защиту от непрофессионалов.

Декларирование продукции требуется для подтверждения соответствия стандартам.

Для торговли, логистики, финансов необходимо специальных разрешений.

https://ok.ru/group/70000034956977/topic/158860235421873

Игнорирование требований ведут к приостановке деятельности.

Добровольная сертификация помогает повысить доверие бизнеса.

Соблюдение норм — залог успешного развития компании.

Нужна камера? установка камер видеонаблюдения на участке для дома, офиса и улицы. Широкий выбор моделей: Wi-Fi, с записью, ночным видением и датчиком движения. Гарантия, быстрая доставка, помощь в подборе и установке.

Need transportation? car transportation service car transportation company services — from one car to large lots. Delivery to new owners, between cities. Safety, accuracy, licenses and experience over 10 years.

I will immediately grasp your rss as I can not to find your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please allow me understand in order that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Discover detailed information about the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore 15710ST via this platform , including price trends ranging from $34,566 to $36,200 for stainless steel models.

The 42mm timepiece boasts a robust design with automatic movement and rugged aesthetics, crafted in rose gold .

https://ap15710st.superpodium.com

Check secondary market data , where limited editions command premiums , alongside pre-owned listings from the 1970s.

Request real-time updates on availability, specifications, and investment returns , with trend reports for informed decisions.

Professional seattle swimming pool installation — reliable service, quality materials and adherence to deadlines. Individual approach, experienced team, free estimate. Your project — turnkey with a guarantee.

Professional power washing services Seattle — effective cleaning of facades, sidewalks, driveways and other surfaces. Modern equipment, affordable prices, travel throughout Seattle. Cleanliness that is visible at first glance.

Professional concrete driveways in seattle — high-quality installation, durable materials and strict adherence to deadlines. We work under a contract, provide a guarantee, and visit the site. Your reliable choice in Seattle.

This platform provides detailed information about Audemars Piguet Royal Oak watches, including market values and design features.

Access data on luxury editions like the 41mm Selfwinding in stainless steel or white gold, with prices starting at $28,600 .

Our database tracks collector demand, where limited editions can command premiums .

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak 15510 or price

Movement types such as chronograph complications are clearly outlined .

Check trends on 2025 price fluctuations, including the Royal Oak 15510ST’s retail jump to $39,939 .

Здесь вы найдете сервис “Глаз Бога”, позволяющий проверить данные о человеке из открытых источников.

Бот функционирует по фото, обрабатывая актуальные базы онлайн. Благодаря ему осуществляется пять пробивов и глубокий сбор по запросу.

https://glazboga.net/

Full hd film izlemek artık daha kolay ve erişilebilir

full film izle 4k https://www.filmizlehd.co/ .

В этом ресурсе доступен мощный бот “Глаз Бога” , который обрабатывает информацию о любом человеке из общедоступных ресурсов .

Инструмент позволяет идентифицировать человека по ФИО , показывая данные из онлайн-платформ.

https://glazboga.net/

Crafted watches never lose relevance for many compelling factors.

Their craftsmanship and tradition define their exclusivity.

They symbolize achievement and refinement while blending functionality with art.

Unlike digital gadgets, they endure through generations due to scarcity and quality.

https://whitesneaker.ru/

Collectors and enthusiasts respect the legacy they carry that no smartwatch can replicate.

For many, collecting them defines passion that goes beyond fashion.

¿Necesitas cupones recientes de 1xBet? En este sitio podrás obtener recompensas especiales en apuestas deportivas .

El código 1x_12121 te da acceso a hasta 6500₽ al registrarte .

Para completar, canjea 1XRUN200 y recibe una oferta exclusiva de €1500 + 150 giros gratis.

https://www.metooo.co.uk/u/6841b8862c79b43252308d8c

No te pierdas las novedades para conseguir más beneficios .

Los promocódigos listados funcionan al 100% para esta semana.

No esperes y maximiza tus ganancias con esta plataforma confiable!

Looking for exclusive 1xBet promo codes? This site offers verified bonus codes like 1XRUN200 for registrations in 2025. Get €1500 + 150 FS as a welcome bonus.

Activate official promo codes during registration to maximize your rewards. Benefit from no-deposit bonuses and special promotions tailored for sports betting.

Find monthly updated codes for 1xBet Kazakhstan with fast withdrawals.

Every promotional code is tested for validity.

Grab limited-time offers like GIFT25 to increase winnings.

Active for first-time deposits only.

https://images.google.as/url?q=https://redclara.net/news/pgs/?1xbet-promo-code-zambia.htmlStay ahead with top bonuses – apply codes like 1x_12121 at checkout.

Enjoy seamless benefits with instant activation.

Гагры: отдых в окружении природы, горных рек и реликтовых лесов

отдых в гаграх 2024 цены http://www.otdyh-gagry.ru/ .

Здесь вы можете найти боту “Глаз Бога” , который способен получить всю информацию о любом человеке из общедоступных баз .

Уникальный бот осуществляет поиск по номеру телефона и предоставляет детали из соцсетей .

С его помощью можно пробить данные через Telegram-бот , используя фотографию в качестве поискового запроса .

пробив авто бесплатно

Система “Глаз Бога” автоматически обрабатывает информацию из множества источников , формируя структурированные данные .

Подписчики бота получают 5 бесплатных проверок для тестирования возможностей .

Платформа постоянно совершенствуется , сохраняя высокую точность в соответствии с законодательством РФ.

Searching for exclusive 1xBet discount vouchers? Here is your best choice to access valuable deals tailored for players .

Whether you’re a new user or a seasoned bettor , verified codes ensures maximum benefits across all bets.

Keep an eye on daily deals to multiply your rewards.

https://wavesocialmedia.com/story5299701/1xbet-promo-code-welcome-bonus-up-to-130

Available vouchers are regularly verified to work seamlessly in 2025 .

Take advantage of premium bonuses to revolutionize your odds of winning with 1xBet.

The game is available in the casino app for iOS and Android and in the mobile version of the Aviator official website. The app and mobile version are optimized and intuitive. The controls are simple and all online casino features are retained. Players can take advantage of bonuses and other features of the chosen online casino. After the first deposit, every new user from India can get 500% up to INR 145,000 in the form of a welcome bonus from 1win. This money will go into a separate bonus balance in your account. Between 1% and 30% of the money you lose in our casino, including when you play JetX, will be returned to your main balance in the form of a cashback. The percentage of cashback depends on how much you lose during the week. 1win JetX offers a thrilling and unique gaming experience that sets it apart from traditional casino games. Instead of the usual slots or table games, JetX features a novel concept where players bet on how high a jet will fly before it crashes.

https://jesus-family.com/read-blog/28530

You will receive an e-mail to confirm your registration, please use the link to confirm you are happy to receive marketing emails. Specialised and sustainable coating binders compatible with all kinds of pigments, offer paper manufacturers high brightness, gloss and rich colour. Traders can potentially refine their strategies and capitalize on emerging possibilities by comprehending the influence of colors on market sentiment. Much like a lottery or casino game, color trading combines chance with strategy to create a unique gameplay experience. Many apps in India offer a user-friendly interface that makes it easy even for beginners to participate. Understanding how to manage risks, maximize your payout, and make smart decisions is essential, especially as colour trading continues to grow in popularity across different parts of India. Let’s have a glance at the principle of functioning of color trade, define its legality, and sort out how to govern risks in colour bargaining.

Searching for exclusive 1xBet promo codes ? Here is your best choice to unlock rewarding bonuses tailored for players .

If you’re just starting or a seasoned bettor , the available promotions guarantees maximum benefits during registration .

Keep an eye on daily deals to elevate your winning potential .

https://snapdish.jp/user/DISH_N762YUM985

Available vouchers are tested for validity to work seamlessly for current users.

Take advantage of exclusive perks to transform your odds of winning with 1xBet.

Сертификация и лицензии — обязательное условие ведения бизнеса в России, обеспечивающий защиту от неквалифицированных кадров.

Декларирование продукции требуется для подтверждения безопасности товаров.

Для торговли, логистики, финансов необходимо специальных разрешений.

https://ok.ru/group/70000034956977/topic/158859922487473

Нарушения правил ведут к приостановке деятельности.

Добровольная сертификация помогает усилить конкурентоспособность бизнеса.

Своевременное оформление — залог легальной работы компании.

В этом ресурсе вы можете найти боту “Глаз Бога” , который способен получить всю информацию о любом человеке из общедоступных баз .

Данный сервис осуществляет анализ фото и предоставляет детали из соцсетей .

С его помощью можно пробить данные через Telegram-бот , используя имя и фамилию в качестве поискового запроса .

пробив телефона бесплатно

Система “Глаз Бога” автоматически обрабатывает информацию из открытых баз , формируя исчерпывающий результат.

Подписчики бота получают ограниченное тестирование для ознакомления с функционалом .

Решение постоянно обновляется , сохраняя высокую точность в соответствии с стандартами безопасности .

Организуйте фотосессию на борту: аренда яхты для съёмок

сочи яхты arenda-yahty-sochi23.ru .

Научно-популярный сайт https://phenoma.ru — малоизвестные факты, редкие феномены, тайны природы и сознания. Гипотезы, наблюдения и исследования — всё, что будоражит воображение и вдохновляет на поиски ответов.

¿Quieres códigos promocionales exclusivos de 1xBet? En nuestra plataforma podrás obtener recompensas especiales en apuestas deportivas .

La clave 1x_12121 te da acceso a 6500 RUB durante el registro .

Para completar, utiliza 1XRUN200 y recibe una oferta exclusiva de €1500 + 150 giros gratis.

https://tysonvgqz96318.blogminds.com/descubre-cómo-usar-el-código-promocional-1xbet-para-apostar-free-of-charge-en-argentina-méxico-chile-y-más-32416028

Revisa las promociones semanales para conseguir más beneficios .

Las ofertas disponibles están actualizados para esta semana.

¡Aprovecha y maximiza tus ganancias con 1xBet !

бесплатные акки стим общие аккаунты стим бесплатно

resume as a engineer https://resumes-engineers.com

бесплатные общие аккаунты стим бесплатные аккаунты в стиме

Looking for exclusive 1xBet promo codes? Our platform offers verified bonus codes like 1x_12121 for new users in 2025. Get up to 32,500 RUB as a welcome bonus.

Activate official promo codes during registration to maximize your rewards. Benefit from no-deposit bonuses and exclusive deals tailored for casino games.

Find daily updated codes for 1xBet Kazakhstan with fast withdrawals.

All voucher is tested for validity.

Grab limited-time offers like 1x_12121 to increase winnings.

Active for new accounts only.

https://mysocialfeeder.com/story4530223/unlocking-1xbet-promo-codes-for-enhanced-betting-in-multiple-countriesKeep updated with 1xBet’s best promotions – enter codes like 1XRUN200 at checkout.

Enjoy seamless benefits with easy redemption.

Мир полон тайн https://phenoma.ru читайте статьи о малоизученных феноменах, которые ставят науку в тупик. Аномальные явления, редкие болезни, загадки космоса и сознания. Доступно, интересно, с научным подходом.

Читайте о необычном http://phenoma.ru научно-популярные статьи о феноменах, которые до сих пор не имеют однозначных объяснений. Психология, физика, биология, космос — самые интересные загадки в одном разделе.

engineer resumes resume software engineer google

Индивидуальные решения для профессионального клининга помещений

сайт клининга https://kliningovaya-kompaniya0.ru/ .

В этом ресурсе вы можете найти боту “Глаз Бога” , который может проанализировать всю информацию о любом человеке из общедоступных баз .

Уникальный бот осуществляет поиск по номеру телефона и предоставляет детали из онлайн-платформ.

С его помощью можно пробить данные через Telegram-бот , используя имя и фамилию в качестве ключевого параметра.

пробив тг

Технология “Глаз Бога” автоматически анализирует информацию из проверенных ресурсов, формируя подробный отчет .

Подписчики бота получают 5 бесплатных проверок для тестирования возможностей .

Решение постоянно совершенствуется , сохраняя скорость обработки в соответствии с требованиями времени .

Şu anda Predictor Aviator yalnızca on bahisçide çalışmaktadır: 1xbet, 1Win, Casinozer, Mostbet, Betwinner, PremierBet, Pin-Up, Betano, Bitcasino ve MrXbet Genel olarak, Aviator tahmincisini kullanmak, bu oyunu kazanma şanslarını artırmak isteyen deneyimli oyuncular için yararlı olabilir. Bununla birlikte, oyunun hala bir şans oyunu olduğunu ve başarıya ulaşmak için tek başına bir tahminciye güvenmemeniz gerektiğini unutmamalısınız. Detaylı Oyun Mekanikleri: Sinyal hilesi, Aviator oyununun nasıl işlediği ve dinamikleri hakkında size derinlemesine bilgi verir. Aviator Signal Bot, oyun verilerini gerçek zamanlı olarak analiz etmek için gelişmiş algoritmalar kullanır. Daha sonra oyuncuya ne zaman ve ne kadar bahis oynayacağını gösteren sinyaller sağlar. Sinyaller, oyunun mevcut trendi, oyuncunun bahis geçmişi ve daha fazlası dahil olmak üzere çeşitli faktörlere dayalıdır.

https://fahadkhanrajin.com/2025/05/27/pin-up-aviator-m%c9%99rc-sisteml%c9%99rinin-f%c9%99rqli-yanasmalari/

Among gamblers from India, Aviator is perhaps the best-known crash game. The ease of use, short round length, and, of course, the possibility to win big helped it achieve a meteoric rise to fame upon the 2019 debut. The Aviator app contains the mobile version of the game. The well-known casino sites such as Parimatch, Pin-Up, or Rajabets, create such programs. $result.appendData?.category_name SportPesa is your premier online casino destination. We offer a wide selection of the latest and greatest slot games and jackpots, alongside casino classics such as Roulette, Poker and Blackjack. The famous crash game Aviator is now available in Kenya. It is known widely – from South Africa to India. Spribe invites interested players to catch the little lucky plane and find out more about crash entertainment.

На данном сайте вы найдете Telegram-бот “Глаз Бога”, который собрать сведения о гражданине по публичным данным.

Инструмент работает по фото, анализируя доступные данные в сети. Через бота можно получить 5 бесплатных проверок и глубокий сбор по фото.

Платформа проверен согласно последним данным и включает фото и видео. Бот гарантирует проверить личность в открытых базах и предоставит сведения за секунды.

Глаз Бога glazboga.net

Такой сервис — помощник при поиске людей удаленно.

Комбинирай дамски блузи с поли, панталони и дънки с лекота

дамски блузи с дълъг ръкав http://bluzi-damski.com/ .

Всё о городе городской портал города Ханты-Мансийск: свежие новости, события, справочник, расписания, культура, спорт, вакансии и объявления на одном городском портале.

Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak 15450ST boasts a

slim 9.8mm profile and 5 ATM water resistance, blending sporty durability

The watch’s timeless grey hue pairs with a stainless steel bracelet for a versatile aesthetic.

The selfwinding mechanism ensures seamless functionality, a hallmark of Audemars Piguet’s engineering.

This model was produced in 2019, reflecting subtle updates to the Royal Oak’s heritage styling.

Available in blue, grey, or white dial variants, it suits diverse tastes while retaining the collection’s signature aesthetic.

Audemars 15450 st

A structured black dial with Tapisserie texture highlighted by luminous appliqués for clear visibility.

The stainless steel bracelet offers a secure, ergonomic fit, finished with an AP folding clasp.

Renowned for its iconic design, this model remains a top choice among luxury watch enthusiasts.

I am really loving the theme/design of your website. Do you ever run into any browser compatibility issues? A number of my blog visitors have complained about my blog not working correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox. Do you have any suggestions to help fix this issue?

Услуги массажа Ивантеевка — здоровье, отдых и красота. Лечебный, баночный, лимфодренажный, расслабляющий и косметический массаж. Сертифицированнй мастер, удобное расположение, результат с первого раза.

Открий дамски комплекти, които подчертават формите и придават увереност

дамски комплекти http://komplekti-za-jheni.com/ .

Трендовые фасоны сезона 2025 года вдохновляют дизайнеров.

Актуальны кружевные рукава и корсеты из полупрозрачных тканей.

Детали из люрекса создают эффект жидкого металла.

Многослойные юбки становятся хитами сезона.

Минималистичные силуэты создают баланс между строгостью и игрой.

Ищите вдохновение в новых коллекциях — оригинальность и комфорт превратят вас в звезду вечера!

https://www.exceldashboardwidgets.com/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?t=2302

resume assistant engineer resume for engineering jobs

buy balloons dubai birthday balloons dubai

Graton Resort & Casino has over 3,000 of the hottest slots. Experience gaming on a whole new level, with a variety of classic titles, video poker games, and progressives. You’ll always find your favorite games here! For those dedicated to an enhanced gaming experience, 3D slots offer an ideal choice. Thanks to cutting-edge technologies, slot game providers can transcend traditional flat reel displays, incorporating 3D models to create an immersive and enjoyable atmosphere beyond the screen. These slots boast diverse themes and in-game mechanics, ensuring players can find a game that suits their preferences. Often inspired by popular movies or TV shows, these slots draw players in with familiar titles and captivating short cut-scenes from beloved films. In today’s era, 3D slots are easily accessible on both desktop computers and mobile devices, allowing players to enjoy the complete gaming experience in the palm of their hand.

https://services.myhappyvacation.co.in/2025/05/27/best-aviator-gambling-sites-in-india-ranked-by-payout-speed_1748349377/

Stinkin’ Rich: Skunks Gone Wild is not just a slot game; it’s a wild escapade into the heart of unpredictability. Get ready to spin, win, and revel in the richness of this unique and entertaining slot experience! Is there a trick to winning at online slots? LOOKING FOR A SLOT TO RATE? Well, Stinkin’ Rich is surely a simple-to-play online slot and comes with multiple useful features. One can enjoy high payouts as wellIf you are playing a slot game for the first time, then give it a try. Similar to any top Starburst casino in NJ, you’ll find PlayStar provides you with two great ways to enjoy Stinkin Rich – Slingo Stinkin Rich or the original casino title. I’ve already touched on what you can expect from Stinkin Rich, but what about the Slingo alternative? Similar to any top Starburst casino in NJ, you’ll find PlayStar provides you with two great ways to enjoy Stinkin Rich – Slingo Stinkin Rich or the original casino title. I’ve already touched on what you can expect from Stinkin Rich, but what about the Slingo alternative?

Займы под залог https://srochnyye-zaymy.ru недвижимости — быстрые деньги на любые цели. Оформление от 1 дня, без справок и поручителей. Одобрение до 90%, выгодные условия, честные проценты. Квартира или дом остаются в вашей собственности.

Свадебные и вечерние платья нынешнего года вдохновляют дизайнеров.

В тренде стразы и пайетки из полупрозрачных тканей.

Блестящие ткани создают эффект жидкого металла.

Асимметричные силуэты возвращаются в моду.

Минималистичные силуэты создают баланс между строгостью и игрой.

Ищите вдохновение в новых коллекциях — стиль и качество оставят в памяти гостей!

http://magazine-avosmac.com/php-mauleon/viewtopic.php?f=5&t=995488

Ваш финансовый гид https://kreditandbanks.ru — подбираем лучшие предложения по кредитам, займам и банковским продуктам. Рейтинг МФО, советы по улучшению КИ, юридическая информация и онлайн-сервисы.

КПК «Доверие» https://bankingsmp.ru надежный кредитно-потребительский кооператив. Выгодные сбережения и доступные займы для пайщиков. Прозрачные условия, высокая доходность, финансовая стабильность и юридическая безопасность.

Сделай сам как сделать ремонт в хрущевке Ремонт квартиры и дома своими руками: стены, пол, потолок, сантехника, электрика и отделка. Всё, что нужно — в одном месте: от выбора материалов до финального штриха. Экономьте с умом!